How useful is mortgage rate history?

Mortgage rate history may sound a pretty boring topic. Indeed, you may subscribe to the Henry Ford school, which believes that all history is bunk.

However, knowing how mortgage rates behaved in the past can help you understand what might happen to them in the future. That knowledge could help you avoid serious mistakes that might cost you thousands.

So read on, as the following information is quite interesting!

Verify your new rate“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” ― Edmund Burke

As a species, we’re pretty disastrous at forecasting. That’s mostly because we’re terrible at remembering the important stuff.

Mortgage rate predictions for 2018 from the experts

It’s been roughly 10 years since the credit crunch triggered the Great Recession, and yet we’re already repeating many of the mistakes that caused both. No matter how many times we’re battered by bubbles, debt crises and cyclical recessions, we either forget the lessons or kid ourselves it’s somehow going to be different this time.

Knowing a bit about history can help clever people avoid the worst consequences of financial forgetfulness and learning about mortgage rate history can stop you from making harmful assumptions about the future.

What moves mortgage rates?

It’s very unlikely your original mortgage lender still owns your mortgage. Typically, your loan will have been packaged up with a pile of others into a mortgage-backed security (MBS) and sold off to investors. There’s what’s called a “secondary market” in MBSs, and it’s quite possible your mortgage will be bought and sold multiple times — without your knowing a thing about it.

10 factors that make your mortgage rate (and what to do about them)

When you hear “investors,” you probably think of Warren Buffet or someone on Wall Street who runs your pension. Buyers of American MBSs are just as likely to be civil servants in Beijing or bankers in London, Tokyo, Singapore or somewhere even more exotic. Nowadays, it’s a global market.

Investors’ changing needs

The aim of all those investors is to have a balanced portfolio. They want lots of exciting, high-yield investments to cash in on the good times. But they also need plenty of ultra-safe, low-yield securities to keep them afloat during stormy periods.

The safest of all securities are bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury. But American MBSs are regarded as pretty safe too. That’s why there’s a close (but far from perfect) relationship between yields on 10-year Treasury bonds and rates on new fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs). They generally move in the same direction, but mortgage rates are bit higher because mortgages are a little riskier than Treasuries. After all, homeowners sometimes default, but the American government never does. At least, not so far.

When economies look threatened, demand for safe securities rises. And that’s something that pulls down yields and interest rates.

For example, suppose that two years ago, you bought a $1,000 bond paying five percent interest ($50) each year. (This is called its “coupon rate.”) That’s a pretty good rate today, so lots of investors want to buy it from you. You sell your $1,000 bond for $1,200.

When rates fall

The buyer gets the same $50 a year in interest that you were getting. However, because he paid more for the bond, his interest rate is now five percent.

- Your interest rate: $50 annual interest / $1,000 = 5.0%

- Your buyer’s interest rate: $50 annual interest / $1,200 = 4.2%

The buyer gets an interest rate, or yield, of only 4.2 percent. And that’s why, when demand for bonds increases and bond prices go up, interest rates go down.

When rates rise

However, when the economy heats up, the potential for inflation makes bonds less appealing. With fewer people wanting to buy bonds, their prices decrease, and then interest rates go up.

Imagine that you have your $1,000 bond, but you can’t sell it for $1,000 because unemployment has dropped and stock prices are soaring. You end up getting $700. The buyer gets the same $50 a year in interest, but the yield looks like this:

- $50 annual interest / $700 = 7.1%

The buyer’s interest rate is now slightly more than seven percent. Interest rates and yields are not mysterious. You calculate them with simple math.

When economies look rosy, portfolio managers prefer less safe and more profitable investments, pushing yields and rates upward.

Inflation

It’s been so long since inflation (rising prices leading to reduced purchasing power) was a major issue in the United States that we’ve all but forgotten how scary it can be. We’ve also forgotten what a big effect it can have on mortgage rates. The inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index or CPI) has been above 4.0 percent only once (2007) in the last 26 years. That was a momentary blip, but between 1974 and 1980, it was over 12 percent for three years.

Do some states have cheaper mortgage rates?

Some fear that inflationary pressure is building again in this country. They point to two inflation risk factors: years of setting low rates by the Federal Reserve, and the possibility that recent tax cuts will cause the economy to overheat. Events may or may not prove them right. But many believe the surge in mortgage rates during January 2018 was largely due to those fears.

You can see why. Imagine how you’d feel if you lent someone hundreds of thousands of dollars for 30 years at a fixed rate of 4.0 percent. Then the inflation rate jumped to 12.0 percent or even just 6.0 percent. You’d lose out big time.

Mortgage rate history and the future

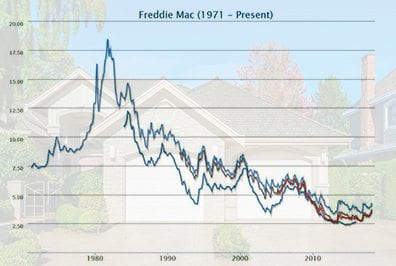

When you want to find historical data about mortgage rates, your best source is probably Freddie Mac’s archives. It’s been keeping accurate, consistent and comparable records since 1971. The information that follows relates to 30-year FRMs.

Lesson 1: Low rates aren’t normal

The first lesson from mortgage rate history is that we are not living in normal times. After eight years during which annual average mortgage rates have been at or near record lows, you might be tempted to think cheap home loans are normal.

You’d be wrong. Rates were over 5.0 percent or 6.0 percent every year between 2001 and 2009. In 2000, they averaged 8.05 percent.

Worse, for the 11 years from 1979 until 1990, they were above 10 percent. Indeed, from 1980 until 1984, they were above 13 percent. That includes 1981 and 1982 when they were over 16 percent.

Lesson 2: 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages may not always be available

In recent years, roughly 90 percent of homebuyers and refinancers have opted for 30-year FRMs. Given that low rates probably won’t last much longer, that seems a smart move for most. (Although those who expect to move on quickly may be better off with a hybrid adjustable-rate mortgage, or ARM.)

7-Year ARM rates perfect for modern homeowners

Now, it’s true that 30-year FRMs have been around since the 1930s. However, this is not the case in most countries outside the US. And even in the US, that’s no guarantee they’ll go on forever.

Borrowing in the 1930s was no fun. You typically had to find a 50 percent down payment, had to pay off or refinance the loan after five or 10 years, and you got an adjustable rate that floated with other loans.

But enough nightmarish mortgage history. Let’s get back to today’s 30-year FRMs. Few other advanced nations offer them, not least because they’re only viable if supported by governments (i.e. taxpayers). And plenty of lobbyists here at home are pressing for their scrapping. For example, Edward Pinto of the Internal Center on Housing Risk at the American Enterprise Institute wrote in Forbes a couple of years ago:

The 30-year fixed rate mortgage should be retired — for good. Despite continued proof that it fails to build up wealth for the most disadvantaged Americans, and that mortgage debt should not be a burden as homeowners approach their 50s and 60s, misguided advocates maintain that the 30-year fixed rate mortgage should be at the core of the U.S. housing finance system.

You’ll remember recent tax reforms kept mortgage interest deductions only after intense political pressure — and still introduced caps on deductions for new mortgages. Change is in the air.

Lesson 3: Inflation is the enemy of low rates

We’ve already discussed the threat inflation poses to low-interest rates. But mortgage rate history underscores that message.

A helpful chart: how inflation changes mortgage rates

The big lesson

Those three lessons add up to one big one: Batten down your financial hatches.

That means putting in place now the sort of borrowing that’s likely to suit you for as long into the future as you can predict. There are plenty of signs the whole home-lending landscape could change in coming years. And mortgage rate history teaches us that landscape might be far from pretty.

What are today’s mortgage rates?

Current mortgage rates are still in the low- to mid-4 percent range, creeping up but affordable. You can find the best deal by comparison shopping, making yourself as attractive a borrower as possible, and perhaps considering ARM loans.

Time to make a move? Let us find the right mortgage for you