Why we’re not hoping for more record-breaking mortgage rates

On March 15, 2020, the Federal Reserve shocked the U.S. by slashing its interest rates a full point and unveiling a $700 billion stimulus package.

Earlier, we wrote about how Fed rate cuts don’t always lead to lower mortgage rates.

But the Fed’s new measure to combat COVID-19 — a $700 billion quantitative easing package — could have a much bigger impact for borrowers.

The last time mortgage rates hit record lows (aside from a brief spell this year) was in 2012. Right in the middle of a huge QE stimulus package to help the U.S. get out of its recession.

The same thing could very well happen again. With the Fed injecting money into the mortgage market, rates could drop back to the low 3s — or even the 2s.

But should borrowers hope for new record-low rates? More stimulus from the Fed could only be a product of prolonged coronavirus impacts

So in other words — a new record low for mortgage rates might be a worst-case scenario. We explain here.

What is quantitative easing?

Quantitative easing (QE) is “the introduction of new money into the money supply by a central bank.” In the Federal Reserve’s case, that means buying up debt from the U.S. market. This introduces more money into the economy, and helps keep borrowing costs low.

QE is meant to spur consumer spending when the economy slows down.

As COVID-19 has brought an abrupt halt to huge sectors of the U.S. economy, the Fed hopes quantitative easing will help increase stability until things return to a more normal state.

As an enormous spender, the Fed can step in to influence prices, as well as yields and mortgage rates. With its current package, the Fed is planning to spend $700 billion buying bonds and securities on markets.

For those keeping an eye on mortgage rates, the important thing to note is that $200 billion of that $700-billion package is reserved for buying mortgage-backed securities (MBSs).

Quantitative easing, MBS, and your mortgage rate

Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are the economic drivers behind mortgage rates. In short, MBS represent the prices investors are willing to pay for mortgages.

More money flowing into MBS leads to lower rates for borrowers (it’s basic supply and demand). That’s exactly what the Fed is aiming for with its $200 billion QE injection into the mortgage market.

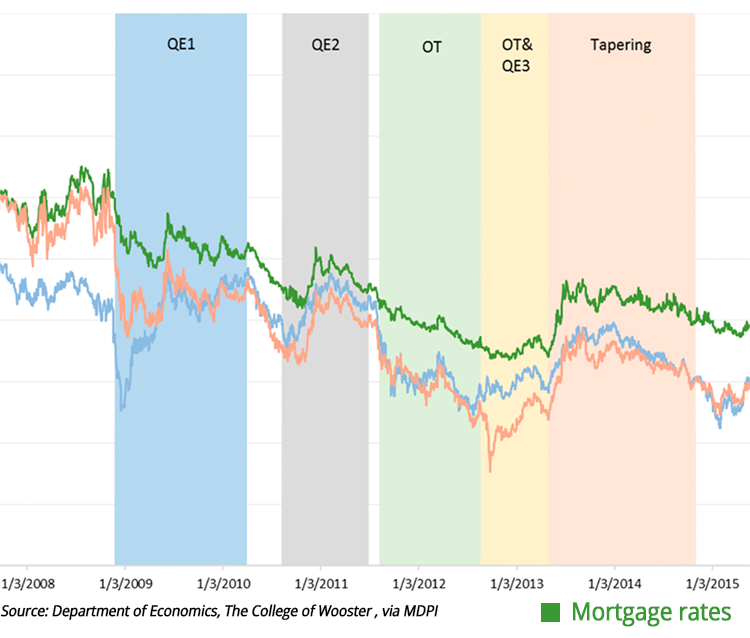

Image: Mortgage rates fell during three periods of QE from 2009-2013, ending with all-time low rates in late 2012.

With all the fuss they make when you file an application, you’d think mortgage lenders were putting up their own money. But that’s rarely the case. Typically, they sell your debt as soon as they can after closing.

What they do is include your mortgage in a whole pile of similar ones and sell them all on a “secondary market”. A secondary market is one that is once-removed from the consumer market: it’s made up of investors that buy consumer mortgage debt in hopes to collect the interest.

Each bundle of mortgages is a “mortgage-backed security.”

Lenders keep an eagle eye on investor demand for MBS. And they set your mortgage rate based on how much they think those investors will pay for the privilege of owning your loan.

>> Related: Here’s what really determines your mortgage rate

Investors are usually happy to buy MBS because all those mortgage payments from qualified borrowers provide a relatively safe income stream for years to come.

Of course, investors know that few 30-year loans last the full three decades. But they rely on them providing a stream for a reasonable time. And they’re willing to shell out for those returns — usually.

Coronavirus turned the system upside-down

The secondary market usually does its part to keep mortgage rates low. The more investor demand there is, the lower rates go for consumers.

But things fell apart during the first half of March 2020. It started so well: Mortgage rates fell to record lows. But that had an unwelcome byproduct.

A tsunami of new applications, especially for refinances, spooked investors.

Investors buy MBS because they want a nice, safe, steady income. But if homeowners suddenly start refinancing in droves — perhaps only months or a year or two after the last time — that nice, safe, steady income evaporates.

So investors voted with their feet. No way would they keep buying MBS with low returns (as a result of low mortgage rates) when they risked reduced profits or even losses on existing bundles through excessive refinancing.

If they were destined to get a low return anyway, why not buy ultrasafe U.S. Treasurys? After all, unlike homeowners, the American government never refinances and (so far!) never defaults, even during recessions and depressions.

Anyway, as a result of fed-up investors, mortgage rates had one of their worst weeks ever by the time Friday, March 13 (appropriately) ended.

>> Related: The race to zero: How mortgage rates got left behind

Will quantitative easing push mortgage rates back to record lows?

Mortgage rates tumbled again the following Monday (March 16), almost precisely mirroring the previous Friday’s disastrous rise.

Some of that may have been down to MBS investors calculating that the previous week’s rises had deterred so many refinancers that it was safe to go back in the water.

But a lot of it was probably thanks to the Fed’s promised intervention.

The MBS market is like any other: If some new purchaser with $200 billion in their back pocket turns up wanting to buy what’s on offer, that extra demand’s going to drive up prices as buyers compete for a finite supply.

However, when it comes to bonds, higher prices automatically and invariably mean lower yields — and, for MBSs, lower mortgage rates.

Yes, that may be counterintuitive. But it’s a fact. If you’d like a fuller explanation, there’s one toward the end of every edition of The Mortgage Reports’ daily “Mortgage rates today” updates.

And the whole point of the Fed’s current QE program is to stimulate a now struggling economy by encouraging consumers and businesses to borrow and spend.

So its intention is to drive all rates, including those for mortgages, downwards.

Mortgage rates and QE — we’ve been here before

The Fed’s bid to push down consumer mortgage rates through QE may well succeed.

Do you remember the last time (before March 2020) when mortgage rates hit an all-time low?

It was toward the end of 2012, and the economy was still struggling to recover from the 2008 financial downturn.

More importantly, the Fed was running its third round of quantitative easing, QE3. That ended in 2013 — as did those record-low mortgage rates.

You’re probably seeing a pattern here. Fed QE programs can do good things for mortgage rates.

But let’s remember the words of the late Harvard economics professor John Kenneth Galbraith, who said:

“The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.”

Anybody who tells you he knows what’s going to happen to the economy is lying.

True, some have better records for forecasting than others. But many of them would acknowledge the luck involved in their predictions. So read the following with a generous pinch of salt.

Are mortgage rates in the 2s possible?

We began by asking whether it was possible that many mortgage rates might soon begin with a “2.”

And the answer’s an unequivocal yes.

Really, it would be a brave forecaster who’d deny the possibility of them eventually starting with a “1,” a zero, or even a negative symbol.

But we hit problems when we try to upgrade the question from whether it’s possible to how likely it is.

You can easily imagine scenarios in which a “2” or a “1” would arise. And such predictions are a lot less out-there than they would have been a few months ago.

But the uncomfortable reality of cheerleading for lower mortgage rates is that they typically occur only when the economy is in trouble. And the lower the rates, the deeper the trouble.

Looking at COVID-19 long-term: Lower rates might be a worst-case scenario

Maybe the Covid-19 coronavirus will miraculously fade away when warmer weather arrives. That happened with the 1918 flu virus. But it returned in the following fall even worse than before. And few scientists think we’ll have a tested and approved vaccine by then.

Chances are, this could bring human and economic costs that are unprecedented in many people’s lifetimes.

We don’t say that to scare you, but simply because it’s important to acknowledge the scale of the problem — and its potential solutions.

The Fed may end up buying more MBSs and taking its own rates into negative territory. And that, plus investors who are increasingly desperate to find safe havens for their money, could easily push mortgage rates to previously unthinkably lows.

But the same circumstances would also land many people in a situation where they can’t take advantage of lower mortgage rates, thanks to temporary or permanent layoffs.

Let’s face it: most of us would prefer a 5% rate and a job over a 2% rate and an unemployment check.

So if you’re waiting for lower rates — or debating whether to buy or refinance at all, given your projected job security — seriously take the long-term impacts of this virus into account.

A lower-rate environment could benefit some. But others may benefit more from locking sooner rather than later — or even waiting until this whole thing is over.

Time to make a move? Let us find the right mortgage for you